There’s a plethora of information about happiness.

There’s a plethora of information about happiness.

My literature search on this subject yielded over 13,000 scholarly research articles and over one thousand books. Advice about how to be happy floods the internet daily with simplistic listicles and click-bait articles that make it all seem so easy.

But their advice, like telling a sad person to think about all the reasons they shouldn’t be sad, or a depressed person to just get up and exercise, doesn’t work. Thinking about the good things in life can sometimes ameliorate sad feelings, but usually, trying to grasp at happiness when in the grip of a depressed mood leads to failure. And while the research on exercise’s positive effect on depression is robust and persuasive, depressed people lack the drive to work out: that’s what depression means.

These suggestions, though well-meant, amount to telling depressed persons to snap out of it—or it’s their fault. This shames the sufferer, making things worse. And the resulting family strife doesn’t help. Well-intentioned spouses and parents who believe that snapping out of it actually is within a depressed person’s power will eventually succumb to exasperation and resignation.

A recent New York Times article gives suggestions for eliminating negative thinking, and paraphrases Rick Hanson, author of Hardwiring Happiness: The New Brain Science of Contentment, Calm, and Confidence: ” it might be helpful to ask yourself if you are accomplishing anything by dwelling on your negative thoughts.”

Depressed people have negative thoughts. Understandable. When we’re depressed, we’re likely to feel hopeless, inadequate, and a failure. While practicing controlled breathing and mindfulness even with your eyes open, as the article suggests, will help, how do we get to the point of making these actions regular parts of daily life? When sadness overwhelms, it is often impossible to follow well-meaning suggestions with regularity. Like New Years’ resolutions, these techniques fade quickly.

When Sadness is Normal

Sometimes sadness is normal. Experiencing a range of feelings in reaction to painful life events is understandable; these life stressors would make most of us depressed. When psychologists see a client for a first appointment, we assess mood, its duration, and the severity of distress. Is the client’s symptoms within normal limits given the precipitant for entering therapy, e.g., a marital crisis, job loss, or death of a family member? We would say a client’s feelings are “within normal limits” when they come to therapy with sadness after losing a loved one.

In my own practice, a former client returned to treatment recently because his wife had just died. He spoke of his inability to shake the feelings of loss and sadness. It had only been four weeks, and he asked me if it is normal to feel depressed, and the question that inevitably follows: how long it will last? It’s okay to feel sad—but to someone grieving, the feelings can be so intense that time stands still. Four weeks can feel like four years.

It’s hard to feel deep emotional distress, of course. Indeed, because suffering is part of the human condition, we’ve devised a vast repertoire of ways to avoid experiencing our painful emotions and worrisome thoughts, including self-medicating by substance use, distraction by Facebook and other media outlets, and much more. Americans account for two-thirds of the global market for antidepressants, which also happen to be the most commonly prescribed drugs in the United States. These drugs can play a vital role in helping many people cope with chronic depression, but all too often these medications are over prescribed or prescribed without looking at inner sources of depression.

When Positive Thinking and Life Coaching Make it Worse

Or, life coaches with little training in mood disorders are prescribing positive thinking the way many physicians prescribe mood stabilizers, but even positive thinking strategies are ways to avoid painful feelings. I have seen the disastrous results of life coaches who work remotely from home, charging enormous amounts of money to people desperate for help. Sadly, these coaches have not laid eyes on the people they propose to help. They are unable to see the dangerous weight loss or weight gain or pick up the nuanced suicidal non-verbal communications.

One client I saw judged himself to be a failure after his six-month life-coaching sessions because he was unable to feel better or do the things the coach was suggesting. When I saw him after his failed coaching experience, he was in a deep depression, his sadness palpable. I asked if he was suicidal and he admitted that he was—something his coach had never asked about. Alerting his partner and suggesting hospitalization was imperative. Alarmingly, he had already seen three different psychiatrists and obtained antidepressants from each, and not one of them had inquired about suicidality.

Another example from my practice is that of a woman who saw a life coach because she hated her job. They talked about the need to follow her bliss and sever ties with her employer. She took this advice, quit her job, and when her unemployment ended, she was unable to find another job. Despondent, she came to therapy to help sort out her feelings about her life and to find a way to understand why she was unhappy at her former job. She needed to understand her role in how she was sabotaging herself. She took the long road to what ultimately brought her fullness and acceptance of life and work.

Accepting Suffering as Unavoidable

Suffering can’t be avoided. (In Buddhism, it’s the first Noble Truth.) But allowing ourselves to express sadness and to accept deep pain will eventually allow these feelings to dissipate; blocking emotions only deepens problems. Also, giving ourselves time to settle into feeling allows us to recognize that they ebb and flow. Through this, we can accept that while old age and death are inevitable, and feeling sad is part of living, suffering is impermanent. By being able to sit with emotions and not get caught up in either rumination or anxious fretting, we develop a steadiness of mind. Meditation works by settling our turbulent thoughts and emotions so that we can titrate them into tolerable moments.

What works

When sadness becomes major depression, positive thinking (and related approaches, such as life coaching) are like putting a Band-Aid on a gushing wound. Facing our pain, learning to bear our suffering, and then doing the deep inner work of understanding our role in our troubles is a way out. It is often slow and filled with obstacles. Here are some steps in the process:

- Become aware of subtle emotions as you experience them. By becoming aware of emotions as you feel them, rather than pushing them away, you will be better able to use them to employ coping strategies.

- When emotions become intense, know that feelings don’t stay that way forever. All emotions are transient. Practices such as regular meditation help us not just to become aware of feeling but also not to indulge them.

- Remember that subtle change is hard to see. A broken bone mends slowly; in the early stages, healing is hardly noticeable on an X-ray.

- Look deeply at ourselves and the role we play in our mood. Doing so opens what is within, leading to understanding and insight.

- Take into account what precipitates depression. Learning to tolerate understandable sadness and some depression helps normalize what we are experiencing. All emotions have a role to play in living well; we must accept and not disown our most difficult feelings.

Who Helps the Helper?

Who Helps the Helper?

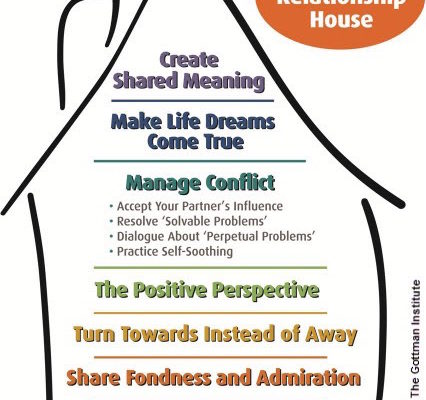

Healthy relationships are built on a strong foundation. In Northern California, where I live, houses are constructed on a solid footing to protect them in an earthquake. If a home is built on soft soil without proper engineering, strong seismic waves will cause a lot of damage. One way that a building is secured is by using lead-rubber bearings, which contain a solid lead core wrapped in alternating layers of rubber and steel. This combination of material is both strong and flexible, reducing damage.

Healthy relationships are built on a strong foundation. In Northern California, where I live, houses are constructed on a solid footing to protect them in an earthquake. If a home is built on soft soil without proper engineering, strong seismic waves will cause a lot of damage. One way that a building is secured is by using lead-rubber bearings, which contain a solid lead core wrapped in alternating layers of rubber and steel. This combination of material is both strong and flexible, reducing damage.