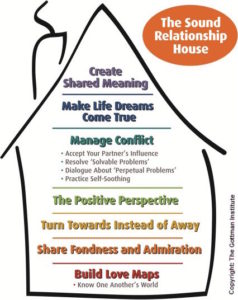

When love is new, we ask questions to get to know our partner well. As Mandy Len Catron wrote for The New York Times in her charming summary of a study 20 years ago by psychologist Arthur Aron, we like learning about the person we love, but over time we forget to keep learning. In Dr. Aron’s study, researchers tried to find out if they could make strangers fall in love with each other by having them ask and answer a series of 36 questions that become more intimate and probing as they went. These questions get deep pretty fast. For people who hardly know each other, this is a low-risk exercise, but for couples once close and now estranged, it’s more challenging. I’ve seen this when I assign couples the Love Map exercise at the end of our first session. Developed by Dr. Gottman, these 62 questions range from super-easy ones such as “Where was your partner born?” to more difficult ones like “Does your partner have a secret ambition? What is it?” I have clients answer the first two or three questions in the office, so I can coach them if they screw it up. As simple as these questions sound, if you don’t know where your partner was born, or what her favorite color, flower, or musical group is, the experience can turn from being fun and playful experience into hurt and disappointment, in turn leading to criticism and increased negative feelings. “She doesn’t know where I was born? After all these years?”

When love is new, we ask questions to get to know our partner well. As Mandy Len Catron wrote for The New York Times in her charming summary of a study 20 years ago by psychologist Arthur Aron, we like learning about the person we love, but over time we forget to keep learning. In Dr. Aron’s study, researchers tried to find out if they could make strangers fall in love with each other by having them ask and answer a series of 36 questions that become more intimate and probing as they went. These questions get deep pretty fast. For people who hardly know each other, this is a low-risk exercise, but for couples once close and now estranged, it’s more challenging. I’ve seen this when I assign couples the Love Map exercise at the end of our first session. Developed by Dr. Gottman, these 62 questions range from super-easy ones such as “Where was your partner born?” to more difficult ones like “Does your partner have a secret ambition? What is it?” I have clients answer the first two or three questions in the office, so I can coach them if they screw it up. As simple as these questions sound, if you don’t know where your partner was born, or what her favorite color, flower, or musical group is, the experience can turn from being fun and playful experience into hurt and disappointment, in turn leading to criticism and increased negative feelings. “She doesn’t know where I was born? After all these years?”

So I set some ground rules: One, it’s okay not to know all the answers—it’s even good—because you can learn something new about each other; it’s an opportunity to re-connect and update in a way that isn’t too challenging. If you don’t know something, make that a topic of conversation, even for just a minute or two.

The second ground rule is to understand that it’s not necessarily the fault of the partner who doesn’t know the answer! Communication is a two-way street. If you don’t take the time, or are passive about seeking knowledge about your partner, or just plain uninterested, preoccupied, or prefer to watch TV, then you need to make a your partner a bigger priority.

Third, I tell couples not to rush through this exercise the night before our next appointment. Take several nights over the week between our sessions to go through five to ten questions at a time, using them as a springboard for getting to know each other again. We refer to this exercise as updating our love maps. Daily obligations leave little time for talk, especially in our wired world, so we can’t expect to know everything about each other when our lives are busy and changing. When couples come back the next week, they usually feel good that they could get most questions right.

Expressing our Dreams Requires Vulnerability

What Dr. Aron’s study points to is that learning the deep, innermost feelings of your partner are what help us love them. When we express those ineffable or unspeakable feelings—those things we hardly tell ourselves—we make ourselves vulnerable, and that is attractive. Often couples have dim knowledge of their partner’s inner world. Dr. Aron’s 36 questions are the type we ask when getting to know someone—and spouses tend to already feel that job is done. Exploring the terrain of the soul with an attentive listener builds an emotional bond rarely experienced for some people with anyone but a therapist. This is why affairs feel rewarding.

As couples get further along in counseling, I have them do what Dr. Gottman calls the Dreams within Conflict exercise. This exercise, which takes place over several sessions, relies on the theory that gridlock results from life dreams in conflict. A powerful part of this exercise is to have each partner fully express a dream or wish that is fundamental to them. For this to happen, each partner needs to feel safe, because the dream is very close to the core of who they are, and it is fragile.

The first step is for one partner to pick a wish or dream, such as the desire for family connectedness, or the wish for adventure and travel, or to express their creativity. Once they think of the dream, their partners will ask a defined series of deliberately redundant questions, in order, without much commentary or discussion. This helps avoid an automatically defensive reaction.

For example, if one partner says “I’d really like to have more thrilling travel,” their partner may immediately respond with objections—and here’s what the mind does—“Oh no! How can we afford it? Will he want to take the kids zip-lining? What if he wants to go to a dangerous country? How can I take time off work? I really hate travel! I’d much rather stay home and have a stay-cation to putter in the garden and get caught up on all my novels… “ and on and on. This stream of thought can take place in seconds, but the effect can last a lifetime for the relationship.

So I ask the listener-partner to just ask the questions, not blurt out their thoughts and fears. Believe me, the stream of thoughts that go through the mind can if articulated, easily lead to squashing their partner’s elaboration of their dream. This Dreams within Conflict process opens up long-shut windows, allowing fresh views of each other, helping return the sweet to a relationship gone sour.

In my practice, I often treat couples who have highly idealistic expectations about marriage. Does that sound contradictory? After all, idealism is romantic, and you need romance for a great marriage. If marriage isn’t just a partnership, but a meeting of souls, then something must be deeply wrong when you have petty disagreements. Soul mates never argue about where the thermostat should be set.

In my practice, I often treat couples who have highly idealistic expectations about marriage. Does that sound contradictory? After all, idealism is romantic, and you need romance for a great marriage. If marriage isn’t just a partnership, but a meeting of souls, then something must be deeply wrong when you have petty disagreements. Soul mates never argue about where the thermostat should be set. A great marriage needs a strong foundation. Remember the story of the three little pigs? The first little pig built his house of straw and the second made his house with wood. The third pig built his house of brick while the first two pigs played, taunting him for working so hard.

A great marriage needs a strong foundation. Remember the story of the three little pigs? The first little pig built his house of straw and the second made his house with wood. The third pig built his house of brick while the first two pigs played, taunting him for working so hard.